Violins and Vertigo

Kurt Gottschalk

Violins and Vertigo

Paul Pinto’s Octet for four or sixteen or so strings

February 2, 2026

There may be nothing more sacrosanct in music than the string quartet, that idealized formation which Goethe likened to a conversation between intelligent people. But the sacrosanct is often best upended. Not destroyed, but more than questioned: Repurposed, deflated.

John Cage, that champion of sound-as-music and sound-as-sound, undermined the practice of composition and performance in his 1983 Thirty Pieces for String Quartet (and indeed through much of his work), using chance operations to determine the notated score, with the four parts not corresponding to one another. Christian Marclay didn’t restrict himself only to strings but referenced the string quartet form in his 2002 work Video Quartet, a montage of movie scenes depicting hands on string instruments, pianos and horns shown on four adjoining screens. Julia Wolfe’s 2019 Forbidden Love was composed for four percussionists playing (with and on) string instruments. For Baobob and Disseminate, Phill Niblock called on the quartet to pre-record four settings of the microtonal scores and play a fifth live, reimagining them as a droning string orchestra.

Other audacious souls over the year have found it appropriate to add a fifth string to the time-honored vn(2)/va/vc (cf. Schubert’s double cello augmentation). Paul Pinto has gone even further, doubling all of the instruments to form a hallucinatory a/v octet, which was performed at CultureHub on Dec. 5 and 6.

Advance info and a brief trailer for String Quartet No. 3 OCTET suggested something about the concept. It didn’t come with a spoiler alert but I’ll provide one here for future beings who might see the piece. It’s a piece that subverts expectations, and one that’s very much seen as well as heard.

OCTET is a string quartet but a mirrored one, or seemingly so, performed at CultureHub Dec. 5 and 6, twice each night in separate performances by the Bergamot Quartet and The Rhythm Method. Each player’s actions were repeated on a video screen directly above them, so maybe it was more rightly a pair of hexadectets. The doubling seems to double in on itself.

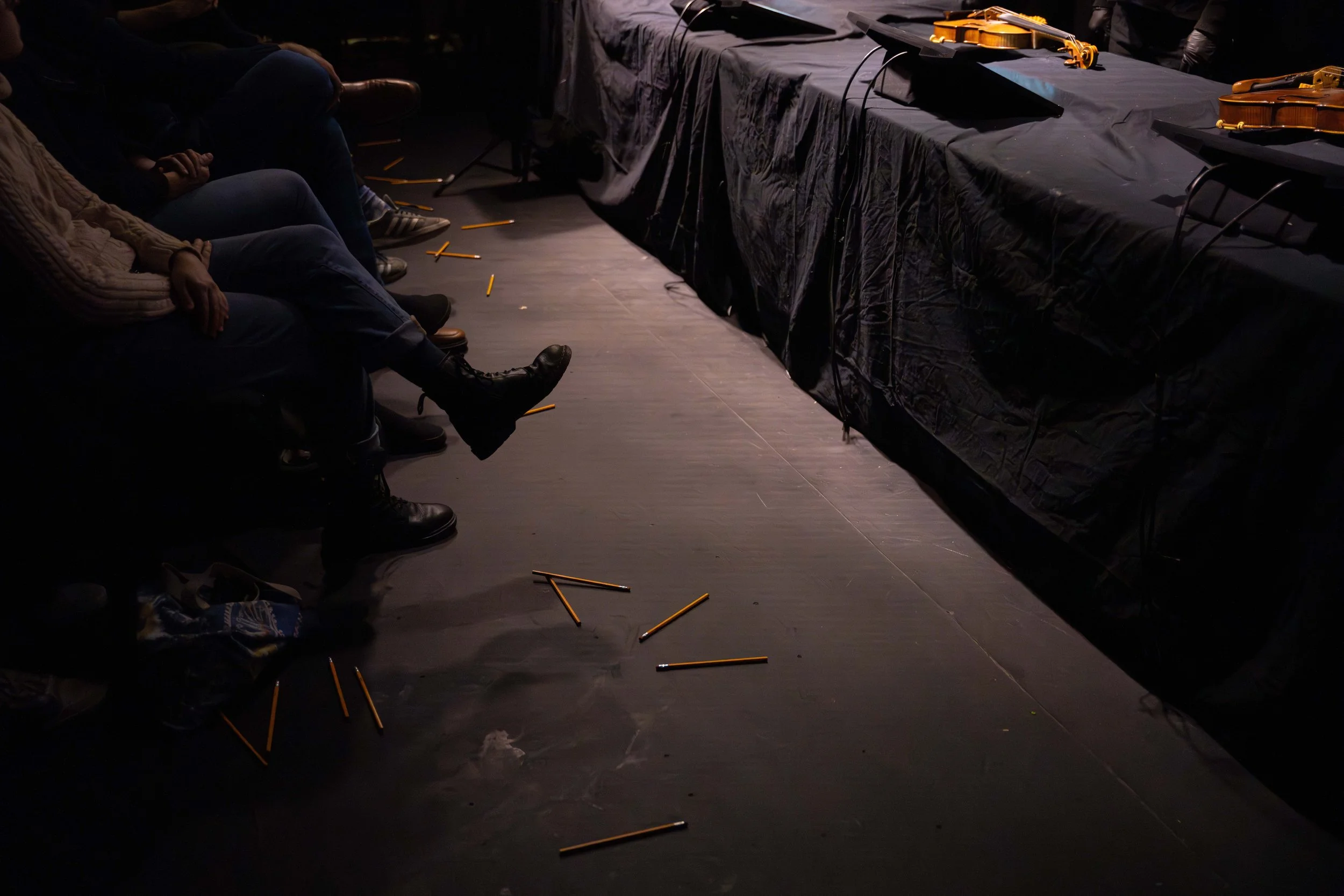

The Bergamot performance on Dec. 6 began with black-gloved hands plucking and strumming the strings of instruments laid out on a long table. Pencils were bounced off the strings and tossed aside. All of this was done in unison, and happening concurrently on four video screens above the players and displaying their hands. Ideas that might commonly be considered “musical” only came slowly. More often it recalled rainfall, or footsteps in gravel. There was sometimes an unsettling tension, but there were also moments of humor. It had peaks and valleys, climaxes and resolutions, not to mention mouth percussion and an inventive use of pencils as bows.

“I’ve never seen (or heard) anything like it” might seem like fairly low-level praise, but how back-handed the compliment is really is a factor of how much the praise-giver has seen in their time. On top of that, one might see something unlike anything they’ve ever seen before on the subway on any given day. Singularity isn’t necessarily a mark of quality. But in point of fact, I haven’t seen anything quite like OCTET, and as someone with a toddler-level thirst for novelty, it was a gleefully perplexing surprise.

Octet possesses the non-integral ability to surprise and surprise again, although as Pinto later tells me, surprise is a “valuable but not integral” part of the piece. When the piece is presented at Roulette in Brooklyn on April 21, it will be performed in its second version, by both quartets and without the video screens. A third iteration is to be played by both quartets and eight video screens. Surprises abound. (No performances are scheduled as yet for the quadruple quartet.)

The most memorable scene in David Lynch’s 1997 movie Lost Highway, at least to my mind, is when The Mystery Man, played by Robert Blake, meets protagonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) at a party. The Mystery Man, with a bitter smile pushing through his pancake makeup, makes a few foreboding comments, but what makes the scene surprising, or even disturbing, for both Madison and the viewer—is the disconnect between voice and physical location. He’s in one place but speaks from another, the voice and mouth don’t match. There’s no cinema trickery involved, it’s just a separate recording of Blake speaking, but it feels wrong. It’s disorienting by suggestion.

OCTET works in similar fashion. It is in large part a piece about gesture, interdependent gesture, right place, right time. The performers execute it like a meticulously choreographed dance, or a high-pressure jewel heist. But it’s also about disconnected gesture, the divorcing of seeing and believing. Pinto infuses the work with an intense intentionality, and that’s what puts the energy into the room. It’s ritual, it’s performance art, and it’s neither, really. But it is an imparting of sonic and visual information, an excitingly visceral actualization of volition.

Kurt Gottschalk is a journalist and author based in New York City. His writings on contemporary and classical music, jazz and improvisation have been published in outlets throughout Europe and America. He produced and hosted the Miniature Minotaurs radio programme on WFMU and currently hosts Afternoon New Music on WKCR.